After two years of COVID unraveled decades of progress, women’s funds have been taking the lead on women’s employment and financial mobility by focusing on innovative childcare solutions.

This piece was originally published via Stanford Social Innovation Review on 5/11/2022.

During the pandemic, a staggering 4.2 million women across the country had to leave the workforce—a full million more women than men. For one thing, layoffs in hard-hit sectors like the leisure and hospitality fields were more likely to employ women; for another, women have had disproportionate caretaking responsibilities while schools, daycares, and senior centers were closed. But while men have now fully recovered—and even outpaced—their pre-pandemic employment rates, women’s employment is not projected to recover to pre-pandemic levels until 2024. While an impressive 467,000 jobs were added in January, women’s overall unemployment remained the same (and the unemployment rate actually grew for Black women).

What can be done? Long before the pandemic, women’s funds—community foundations created with the goal of accelerating progress for all by investing in the leadership of women and girls, especially Black, Latina, Native American, and other women and girls of color—have been at the forefront of deploying capital to organizations working towards women’s underemployment solutions. But before the pandemic, they weren’t getting the visibility, traction, or funding they deserved.

Unfortunately, ignoring causes that serve women is a well-documented problem in philanthropy. Women and girls make up 51 percent of the world’s population, yet women’s and girls’ organizations receive less than 2 percent of all philanthropic giving. The stats are even worse for funds supporting women and girls of color. Of the $67 billion of charitable donations made by foundations in a single year, less than 0.02 percent was specified as benefiting causes that support Black women and girls.

The women’s funds we support through the Women’s Funding Network have long been on the frontlines fighting for changes like childcare initiatives. The same issues affecting women during the pandemic existed before, of course, even if the scale has been magnified exponentially.

Like many individuals in the communities they serve, women’s funds experienced significant financial challenges at the onset of the pandemic, with almost a third finding themselves in danger of closing in 2020. However, through leveraging investments from larger foundations, government, and other funders, preliminary data suggests that women’s funds not only recovered from these initial losses but, on average, these organizations’ fundraising efforts led to double-digit growth in their operating and grantmaking budgets by 2022 when compared with pre-pandemic levels. Specifically, mid-sized funds with grantmaking budgets between $100k and $1M, saw an average of 43% growth in grantmaking budgets from 2019 to 2022. This influx of new funds allowed them to deepen their focus and work on core issues affecting women during (and before) the pandemic.

Starting Local

Long before the pandemic, the Women’s Foundation for the State of Arizona (WFSA) lobbied their state to pass legislation that would help moms maintain their childcare financial assistance while enrolling in full-time education and training programs that could equip them for higher-wage jobs and self-sufficiency. Prior to the passing of Arizona HB 2016 (which didn’t pass until 2021), moms could access childcare financial assistance only if they worked qualifying jobs, but not if they pursued more education to escape the trap of low-wage jobs.

While HB 2016 initially stalled, WFSA scaled up a local pilot program to prove their case. With $115,000 in seed funding, they were able to launch “Pathways for Single Moms” in Tucson. In partnership with Pima Community College and regional nonprofits, the Pathways program removed obstacles low-income single moms face when going back to school by providing the opportunity (which included access to quality childcare, a monthly stipend to supplement income lost while in the program, and education/career coaching), to earn a one-year technical certificate in one of 36 growing fields they had identified within the state. In their early pilot cohorts, they helped small groups of women complete their certificate. And they were able to show that the state saves $20,000 for every family who no longer has to be on public benefits. In the long term, this translates to millions of dollars that can be reallocated to other programs or to this program to continue to get families out of the cycle of poverty.

The bill was finally signed by Governor Ducey, but as the pandemic continued to rage, WFSA got a call from the governor’s office, which had taken notice and wanted to expand the Pathways program—rapidly. In 2022, they were awarded $4.2M in funding to scale it statewide.

“With this funding our nonprofit partners can focus on running the program instead of constantly fundraising for it,” says Dr. Amalia Luxardo, CEO of WFSA. “This will cover hiring and paying staff plus all wrap-around services that the participants need.”

This was possible because WFSA had already done the work to show the effect these types of programs could have. For years they had focused on the intersection of the high cost of childcare and access to post-secondary education for single moms as a workforce development opportunity that could help end the cycle of poverty. Their ability to move fast at the state level is a testament to the foundation they had already laid at the local level, even when funding was sparse.

Disrupting the Norm

Another fund that was able to turn its pre-pandemic work into a lever for growth when crisis hit was the Women’s Fund of Central Ohio (WFCO), who have made it their mission to fund groups who are the least likely to receive institutional dollars.

“We’ve been talking about childcare as one of the major levers of inequity for several years,” says Kelley Griesmer, President & CEO. “We like to fund when no one else will, so we can help these organizations get off the ground. Once they’ve proven their results, they can take that to larger funders for more support,” she says. “And we’ve seen great success with this model over and over again, having deployed more than $4 million since we were founded 20 years ago.”

During the pandemic, WFCO utilized a $30,000 pandemic recovery grant to launch their first-ever immediate impact grantmaking initiative. Employing best practices from experts in trust-based philanthropy, this new initiative quickly funded mini-grants ($2,500 or less) to frontline programs responding to the COVID-19 crisis (with a significant amount of funding directed to programs led by and for women of color, refugees, and New American populations.)

In order to fund these nonprofits, WFCO used their participatory grantmaking model, which includes community stakeholders in the funding decision-making process.

“According to studies, participatory grantmaking promotes social justice, equity, and democratized philanthropy by bringing diverse lived experiences to the decision-making table.”

Kelley Griesmer, President & CEO, Women’s Fund of Central Ohio

But what they did differently during the pandemic was engage those grant readers on a new level. “We created an opportunity within the grant reviewing experience to engage grant readers as grassroots donors and fundraisers, creating a more diverse donor pool within our organization,” Griesmer explains. Through this strategy, they created opportunities for donors, ranging from first-time donors to major donors, to think about equity and why it’s critical to invest in programs led by and for women and girls of color. When the readers saw the immense need and the caliber of the organizations submitting applications for immediate support, they pitched in another $10,000 that day.

“This is disruptive philanthropy,” says Griesmer. “We’re learning how to be as bold as possible to make change.” As a result, they were able to immediately fund nearly $30,000 to 19 organizations and initiatives on the frontlines of COVID-19 serving women and girls in central Ohio.

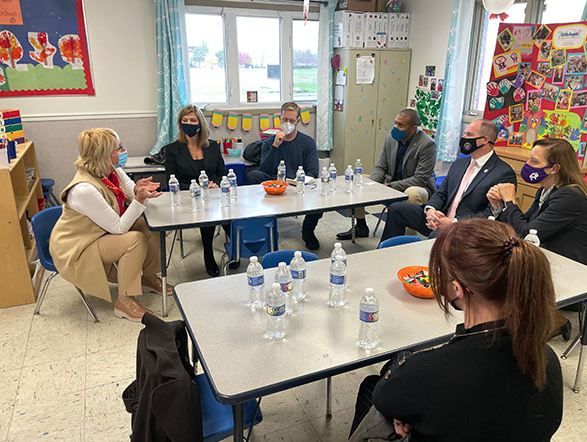

A Seat at the Table

Above all, funds like these had already identified childcare expenses as a primary boulder in the path of working women and set out in scrappy ways to validate paths around it. The pandemic has provided the clarity and attention necessary to help these organizations get the recognition they need from policy makers and big philanthropy to do their work on a broader, more impactful scale. It’s no wonder that during the past two years, several CEOs of women’s funds have been called to sit on local task forces focused on addressing the issues the pandemic brought to bear—the very issues they had already been designing and funding solutions for. States were desperate for programs that could be implemented with speed and rigor—and yield big results. Women’s funds were at the table because they had the data, the connections to local groups, and a deep understanding of how to make tangible progress during a time of crisis.

For example, Dawn Oliver Wiand, president and CEO of the Iowa Women’s Foundation (IWF), was appointed to Governor Reynolds’ Childcare Task Force and helped make informed recommendations for long-term solutions. “COVID really shined a light on what we were doing,” says Wiand.

“We’d been talking about childcare as an economic and workforce issue but everyone only saw it as a family issue. Then, when the pandemic hit, people couldn’t ignore that this is an economic issue if we’re going to bring women back into the workforce.”

Dawn Oliver Wiand, president and CEO of the Iowa Women’s Foundation

Since 2017, IWF has been supporting and funding local community, educational, and job training programs throughout the state to increase women’s economic security by decreasing the workforce gap through access to quality, affordable childcare through their Building Community Childcare Solutions Fund.

As the childcare crisis unfolded, Iowa was facing the same issues as the rest of the country: Women who were essential workers still needed childcare. But in many cases, even when spots were available, the care workforce wasn’t there to support it. IWF was able to raise nearly $80,000 in grant funds to quickly launch in partnership with the Childcare Resource & Referral’s Childcare Ready program—a no-cost fast track for professional childcare training series—as a direct effort to increase the number of childcare workers across the state. As a result of the initial program, there are now 78 more childcare slots, and once the final applications are approved for the rest of the program participants, that will lead to up to 350 additional slots. It’s this type of quick thinking that leverages women’s funds existing understanding of the local landscape and solutions.

The pandemic also propelled IWF to adjust its funding strategy. “Before, we were primarily funded by individual donors that came through corporate-sponsored events and direct mail campaigns,” says Wiand. But when the pandemic canceled events, IWF went to those corporate sponsors and asked for the funding directly, something they hadn’t done before. As a result, they were able to raise over $95,000 in six months from corporations and a direct mail campaign. These additional funds enabled them to increase their grantmaking by 10 percent.

Sheri Scavone, CEO of the Western New York (WNY) Women’s Foundation, sat on Congressman Tom Reed’s Economic Recovery Taskforce, lobbying to make sure childcare concerns were heard and understood at the highest federal level. Before the pandemic, the WNY Women’s Foundation was already running a strategic initiative called “MOMs: From Education to Employment,” giving grants to community colleges that work to support single moms as they complete a college education and secure a family-sustaining job. They knew what was working and what moms needed on the local level to not drop out during the pandemic.

“We’re registered lobbyists so we’re able to be a conduit from the federal to the state to the local level,” says Scavone. And lobby they did: Of the $2.3B in funding the state received in the last stimulus package, $100 million went to roughly 17,000 childcare businesses in order to keep them open. With funding from Erie County’s CARES funds, WNY Women’s Foundation was a thought leader for the creation of 72 virtual learning centers throughout Erie County in New York State (the second largest county after New York City), which allowed children who were in remote schooling but had parents that worked, especially essential workers, to have a safe place with internet access to attend their classes for much of the 2020-2021 school year.

“As a leader in the Empire State Coalition for Childcare, WNYWF has actively engaged those most impacted by the pandemic—in this case childcare providers, and they’ve been empowered to have a voice in all of this. We can be that conduit; a trusted voice that’s able to back it up with data. The pandemic strengthened our own resolve in our relevance. There are so many things that would have never happened, albeit for our being at the table and using our relationships and data. We’re in a unique position to call things out and provide solutions.”

Sheri Scavone, CEO of the Western New York (WNY) Women’s Foundation,

From legislative work to grassroots fundraising to immediate impact giving, it’s clear that women’s funds are pioneering solutions already at work that have a measurable, sustainable, and life-altering effect on women. And after the setbacks of the last two years, it’s time we start providing greater funding to create the changes we need for women to be able to not just match where we were prior to the pandemic, but surpass it.

About the Author

Elizabeth Barajas-Román is the president and CEO of the Women’s Funding Network, the world’s largest philanthropic alliance for gender equity.